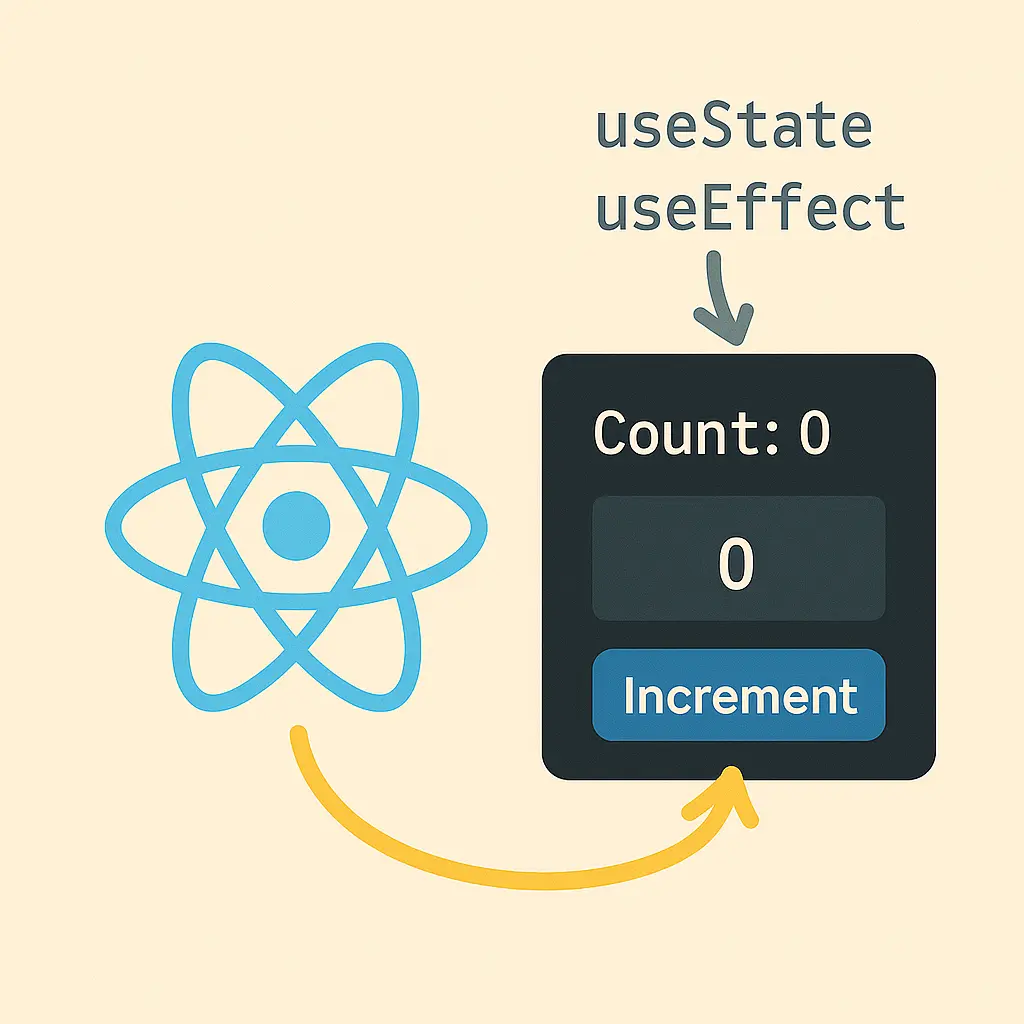

Part 1.3 — Managing State: useState, useEffect, and Data Flow

If components are the structure of your app, state is its heartbeat.

Every time data changes — a button click, a form submission, a fetch from your backend — React re-renders parts of the UI to stay in sync.

Let’s explore how React manages that behavior through two foundational hooks: useState and useEffect.

1. What Is “State”?

State is data that changes over time inside a component.

Examples:

The value of a text input

Whether a modal is open

A list of fetched users

Without state, your React app would be static HTML.

2. useState: Declaring Reactive Data

useState is the simplest way to store and update local component data.

import { useState } from 'react';

export function Counter() {

const [count, setCount] = useState<number>(0);

return (

<div>

<p>Count: {count}</p>

<button onClick={() => setCount(count + 1)}>Increment</button>

</div>

);

}When you call setCount, React schedules a re-render.

Your component updates automatically — no manual DOM manipulation.

TypeScript tip: Always type your state explicitly for clarity and safety.

3. Updating State Safely

React batches updates and re-renders efficiently.

If you need the previous state value, use a callback:

setCount(prev => prev + 1);This prevents race conditions when multiple updates happen quickly.

4. Derived State and Conditional Rendering

You can compute UI based on state:

const [isOnline, setIsOnline] = useState<boolean>(true);

return (

<div>

<p>Status: {isOnline ? '🟢 Online' : '🔴 Offline'}</p>

<button onClick={() => setIsOnline(!isOnline)}>Toggle</button>

</div>

);Best practice:

Keep state minimal — store the source of truth, not every computed detail.

For example, store items and calculate itemCount = items.length dynamically.

5. useEffect: Handling Side Effects

React components must be pure — they shouldn’t perform side effects like fetching data or modifying the DOM during rendering.useEffect handles these operations after the component renders.

Example — fetching data from a REST API:

import { useEffect, useState } from 'react';

interface User {

id: number;

name: string;

}

export function UserList() {

const [users, setUsers] = useState<User[]>([]);

const [loading, setLoading] = useState<boolean>(true);

useEffect(() => {

fetch('/api/users')

.then(res => res.json())

.then(data => {

setUsers(data);

setLoading(false);

});

}, []); // Empty array = run once on mount

if (loading) return <p>Loading...</p>;

return (

<ul>

{users.map(user => (

<li key={user.id}>{user.name}</li>

))}

</ul>

);

}Key insight:

useEffectruns after the first renderThe second argument (

[]) defines dependencies — when the effect should re-run

6. Dependency Arrays Explained

Dependency arrays tell React when to re-run your effect.

[]: Run once on mount[userId]: Run whenuserIdchangesNo array: Run on every render (⚠️ avoid unless necessary)

Example — reacting to prop changes:

useEffect(() => {

document.title = `Welcome, ${name}`;

}, [name]);7. Cleanup in useEffect

When your component re-renders or unmounts, useEffect can clean up — useful for subscriptions, timers, or event listeners.

useEffect(() => {

const id = setInterval(() => console.log('Tick...'), 1000);

return () => clearInterval(id); // cleanup

}, []);Without cleanup, these side effects can leak memory or run forever.

8. Common State Patterns in Real Apps

1. Form Handling

const [form, setForm] = useState({ name: '', email: '' });2. Loading + Error States

const [loading, setLoading] = useState(false);

const [error, setError] = useState<string | null>(null);3. Derived Booleans

const isDisabled = !form.name || !form.email;You’ll reuse these patterns constantly when building CRUD frontends connected to your NestJS backend.

9. Pitfalls to Avoid

❌ Don’t mutate state directly (

count++) — always use the setter.❌ Don’t include non-deterministic dependencies (like functions) in

useEffectunless memoized.❌ Don’t fetch inside render — use

useEffect.✅ Keep each effect focused on one responsibility (fetch, subscription, or timer).

10. Integrating Backend Data Later

In later parts, your useEffect calls will fetch data from your NestJS REST API, not hardcoded URLs.

The flow will look like:

React Component → fetch('/api/tasks') → NestJS Controller → Prisma → PostgreSQLThis post builds the foundation for that interaction — teaching React when and why to update.

11. Wrapping Up

You’ve learned:

How to declare and update local state with

useStateHow to perform side effects with

useEffectHow to control data flow cleanly in React + TypeScript

Next, in Part 1.4, we’ll handle events and forms — connecting user input with your app’s state safely and efficiently.

Related

Part 3.5 — Shaping API Contracts for the Frontend (React Integration)

Your API becomes truly useful only when the frontend can rely on it. In this post, you’ll learn how to shape consistent REST contracts, shared types, and error formats for React applications.

Part 2.5 — Consuming REST APIs with Shared Types & Error Handling Strategies

Real-world frontends need safety: typed API responses, predictable errors, and consistent client logic. This post teaches you the patterns professionals use to integrate React with REST cleanly.

Part 2.4 — UX State: Loading, Error, and Empty States in React

A React app becomes truly usable when it handles all states gracefully: loading, error, empty, and success. In this post, you’ll learn the UX patterns professionals rely on.

Comments